Starting conversations on Female Genital Mutilation

Here are some statements for you, which ones did you think these were true?

FGM is a religious obligation.

NO, IT IS NOT.

FGM performed by a professional health care provider does not risk harm.

YES, IT DOES.

FGM can improve fertility.

NO, IT CAN NOT.

FGM is a violation of human rights.

YES, IT IS. YES, IT IS. IT IS.

But what exactly is FGM? The abbreviation for Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting, FGM/C as defined by WHO, can be understood to include all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, and also constitutes any other injury to the genital organs of females caused by non-medical reasons. It is often a misunderstood and broad range of practices affecting more than 200 million girls and women, concentrated in prevalence in around 30 countries in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. It is not just a one-time practice that result in excessive bleeding, problems in urination, and even death but also associated with long-term consequences leading to the development of cysts and infections, complicated child birth, and furthermore even an added risk of death the new-born.

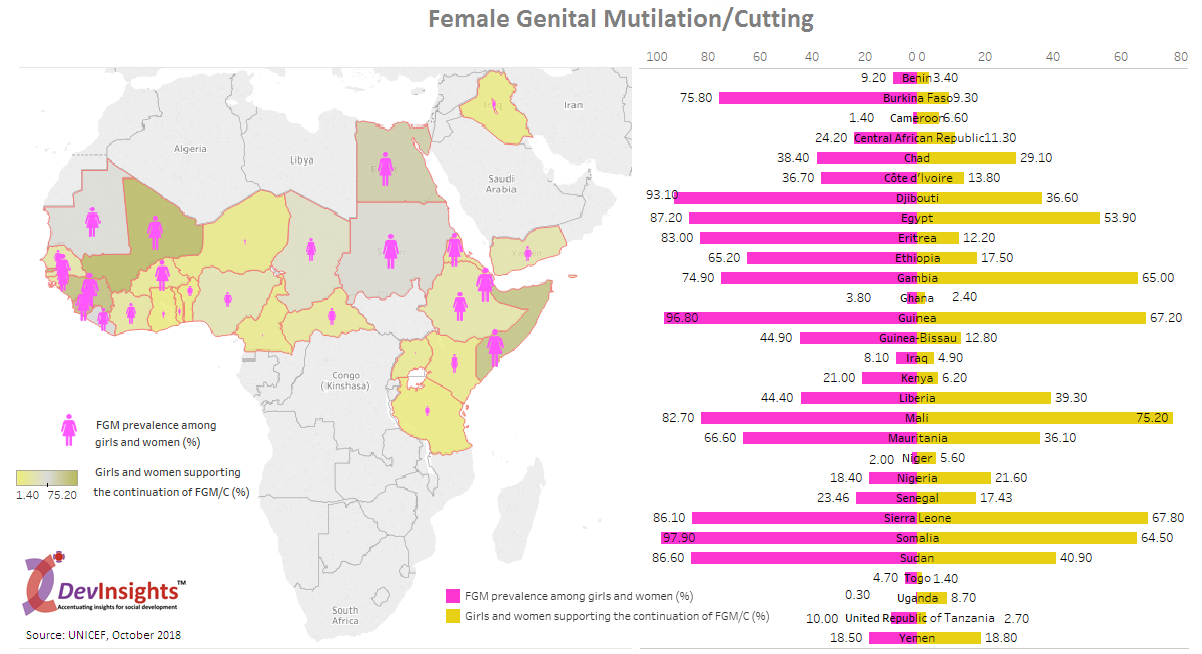

To these statements, logic dictates the simplest of questions, then why does such a violent and heinous practice still exist? It exists because it is called to be a ‘tradition’ and a ‘norm’ that in line with the many other dominant patriarchal ways of the world, puts the onus of upholding the status and honour of a family on the girl, making them acceptable for marriage. Data shows that the practice is concentrated from Horn of Africa till the Atlantic Coast, wherein the highest prevalence levels (in girls and women between ages of 15 and 49) of FGM/C above 90 percent depict almost universality in Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti and Egypt. Egypt has the largest incidence with around 27.2 million women reported to have undergone the procedure. While the practice not concentrate is also prevalent in in countries of Europe, USA, UK, India, Indonesia and more, more alarming is the fact that the prevalence is increasing in these countries too. Furthermore, other factors such as regions, ethnic groups, urban or rural setting, education and wealth status of women reflect differences of prevalence in the concentrated countries.

In almost all countries, the majority procedures are performed by traditional practitioners but there has been a rising trend of health personnel performing it in some countries, such as Egypt, Sudan, and Guinea. More horrifying aspects associated with the practice are that most cases of FGM/C are undertaken at home with a blade or razor and largely the girls were cut either before the age of 5 or between the ages of 5 and 14. The highest levels of support for the practice amongst women is found in countries of Mali, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Gambia, Somalia and Egypt, also the sites with some of the highest prevalence, reflecting on some linkages between the commonality of the practice and attitude. This pose another problem wherein the girls and women who undergo this do not have contact with those who have not been cut or could be in danger making information sharing difficult. Some of the most commonly cited benefits were gaining social acceptance, better marriage prospects and preservation of virginity.

Hope still prevails as the growing data suggests of increasing national and grassroots commitments to end FGM/C that are enhancing the scope for global commitment towards its elimination. February 6 has been marked as the International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation. There have been increasing efforts to generate reliable data on the practices and examine and analyse the differentials across countries so as to inform the formation of policies and programmes targeted to end it. While there are still supporters for its continuation, majority girls and women and boys and men think the practice should end. Increasingly, boys and men are being targeted to end FGM/C and empower girls in their communities. Educational campaigns, constitutional decrees, public discussions have been some of the ways to dispel the myths associated with the practices and make the people understand about its consequences. Not just the people practicing, but health care professionals involved are also being targeted to generate awareness to not perform such procedures.

There is progress and there is yet a long way to go, but striving forward would spare millions of girls from what generations of women before them went through.